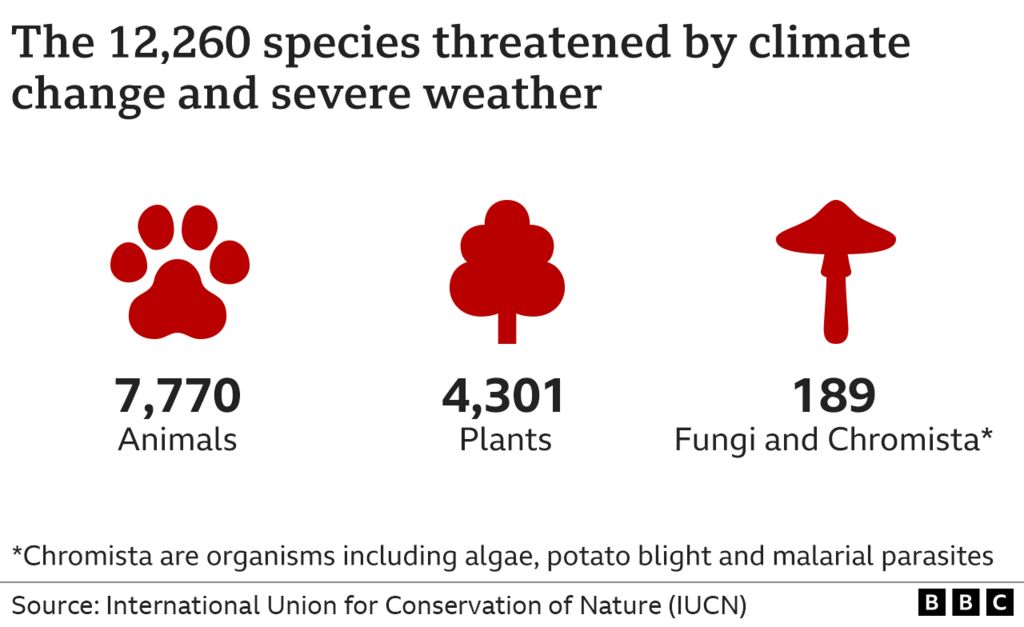

Discussion of climate change usually focuses on the danger to people, but wildlife is equally affected, if not more so. The crisis is contributing to the risk of extinction of 12,260 threatened species, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recently calculated.

Here are three women who dedicate their lives to saving one of those species – the mountain gorilla, the Chinese pangolin and the leatherback turtle.

Mountain gorillas

When Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka began working in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in 1996 the number of mountain gorillas was in sharp decline. But under her care, their fortunes have revived: the population has increased by two-thirds and now stands at 500.

A similar number inhabit the Virunga Mountains, further west, including the Virunga national park in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Kalema-Zikusoka’s success is one reason why the mountain gorilla was downgraded from critically endangered to endangered in the 2018 IUCN “red list” of threatened species.

But this has not allowed her to relax.

Since 1950, temperatures in Uganda have risen at a rate of nearly a quarter of a degree Celsius per decade, leaving mountain gorillas struggling to quench their thirst. One way they do this is by eating plants with a high moisture level – but these moist plants have been becoming scarce and shifting to different altitudes.

“That could be one of the reasons why they come down to the lower parts of the mountain more often, to people’s farms, for banana trunks which have lots of moisture. And that has resulted in increased conflict with farmers,” Kalema-Zikusoka says.

She and her team are now working on expanding the area of the national park, by buying more land from farmers, so that the gorillas can freely move further up or down the mountains in search of food and water.

It was while she was a student at the Royal Veterinary College in London, in the 1990s, that Kalema-Zikusoka began her work on apes, and learned that they were threatened by loss of habitat and human-borne diseases.

She met her first mountain gorilla, named Kacupira, while carrying out field work.

“He was very calm and accommodating and when I stared into his deep brown eyes, I felt a deep connection,” says the 53-year-old, who now lives in Entebbe, not far from the national park.

Soon after graduating she became Uganda’s first wildlife vet, working with Uganda National Parks, which later became the Uganda Wildlife Authority.

As climate change has accelerated, the spread of human diseases to the gorilla population has increased.

This is partly a result of higher temperatures, but also of drought, because in their search for water humans are reaching deeper into the national park, and exposing apes to their illnesses.

Gorillas have caught scabies, giardia (a parasite that causes diarrhoea), intestinal worms and respiratory diseases including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) from humans.

The team therefore constantly carries out tests on gorilla faeces to check on their health.

“If we find any alarming infection, we make sure the gorillas are treated,” she says.

There are now concerns that gorillas could be infected by malaria, which is increasingly common in the human population as a result of climatic changes and growing numbers of mosquitoes.

Kalema-Zikusoka’s organisation, Conservation Through Public Health, helps community health workers to reach homes in villages around the national park. Her mantra is “one health” – in other words, keeping both humans and gorillas healthy, so that they don’t infect each other.

“We believe if people are healthy so will the gorillas be.”

Pangolins

As a zoology student in Kathmandu in 2008, Tulsi Suwal used to attend classes carrying her son, then a toddler, on her back.

One day, as she was doing field work outside the city, she saw an animal doing the same thing – it was a Chinese pangolin, one of eight species of the scaly nocturnal mammal.

“It was doing just what I used to do then,” says Suwal. “It was a life-changing experience, and I decided to focus on this species.”

Conservation organisations say pangolins are the most poached animal in the world. This is mainly because their scales are used in traditional Chinese medicine, though some are also eaten.

But now this species, categorised as critically endangered in the IUCN red list, is also threatened by climate change.

In the foothills of the Himalayas, the danger comes from forest fires. Now more frequent and more intense, they destroy ground vegetation and parch the earth, which kills the ants and termites that pangolins survive on.

Smoke from the fires also penetrates the pangolins’ burrows, forcing them out into the open even in daytime.

“And that is when they are either poached or easily fall prey to predators,” says Suwal.

The Small Mammals Conservation and Research Foundation, which she founded, therefore focuses on preventing forest fires wherever pangolins are found in Nepal.

Measures include creating fire lines – strips of vegetation-free land that prevent fires from spreading – and replacing some broadleaved trees with native conifers so fewer dead leaves accumulate on the ground.

“We are also helping local communities with technology and finance to collect dry leaves and turn them into compost that they can use in farming,” says Suwal.

Refilling dried-out ponds, through canals linked to nearby rivers or other water resources has also helped contain forest fires while giving pangolins valuable access to drinking water.

All this has helped to keep forest soil moist, which ensures pangolins find ants and termites to eat.

For farmers, pangolins do useful work to keep these pests in check, so local communities are increasingly supporting Suwal’s measures.

“They are such harmless animals. They just curl up like a ball when they feel threatened, but they can’t protect themselves from the impacts of climate change,” says Suwal.

Leatherback turtles

As Pacific islanders face an existential threat from rising sea levels, Anita Posola has an additional worry: how to prevent leatherback turtle eggs getting washed away from the beaches of the Solomon Islands.

The IUCN red list categorises the species as vulnerable rather than endangered at a global level, but the sub-population in the Western Pacific has shrunk by 80% in recent decades, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Getting tangled up in fishing gear or deliberately caught by humans for food remain the biggest dangers to the leatherback turtle, but storm surges and rising sea levels are an increasing hazard.

It’s important that mother turtles nest above the high-tide mark to prevent their eggs being inundated or washed away, but that mark is now constantly rising.

“This is all very sad. I want to revive their population so that my children are able to see them around in the future,” says Posola, a ranger at the Haevo Khulano conservation area in the Solomon Islands.

So when she and her team notice that turtles have nested below the high water mark, they dig into the sand to rescue the eggs and move them to a safer place.

“But knowing where the turtles have nested is the key, and that becomes a major challenge during night shifts, or when the weather is bad,” says the 32-year-old.

As a child she wanted to be a nurse, and says that her current role isn’t so very different.

“I may not be a nurse, but working in turtle hatcheries, protecting eggs and baby turtles being born feels a little bit like nursing.”

Last November, however, one of the hatcheries provided less protection for the eggs than Posola had hoped. A storm surge combined with a high tide swept over the top of it, and destroyed most of the eggs.

“This was the highest point of the sea beach. We can’t relocate the nests any further,” Posola says.

Her team then built a defensive barrier with sandbags, which has so far kept the hatchery dry.

Rising temperatures are another problem, as warmth influences the sex of the turtle hatchlings. If the surrounding sand is above 31.0C (88.8F) the young will hatch as females, according to the NOAA, while if it is below 27.7C they will be male. Between the two extremes the result will be a mixture of both sexes.

The danger is that in a warming world male turtles will become a rarity, leading to a population collapse.

For this reason, hatcheries are positioned in an area of partial shade, which results in cooler sand.

But measuring and maintaining accurate nest temperatures has been a challenge, and the rangers are working with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), an international conservation organisation, to install the right equipment.

Thanks to the rangers, annual nest numbers of the leatherback turtles in Posola’s conservation area have more than tripled in 10 years, the TNC says, while the relocation of nests saves the lives of more than 3,000 hatchlings every year.

Anita Posola is proud that so much is being achieved – and often, these days, by women.

“Until a few years ago, rangers on the island used to be only men,” she said.

“But now we have an all-women rangers’ team working day and night.”

Source : BBC